A Cautionary Tale: the representation of women in the Queensland Parliament

Carole Ford

My presentation should probably be titled: Ah, so you’re the woman!

Unlike traditional accounts, names and dates have not been changed to protect the guilty.The setting:

Towards the end of 2011, the political manoeuvring in the shadows of the Queensland state election indicated that a potential change in the representative landscape was imminent. Early indicators suggesting that there were ominous signs for women prompted me to write an op ed article for the Brisbane-centric Courier Mail newspaper. In this context I acknowledge the editor of viewpoint for her encouragement and support.

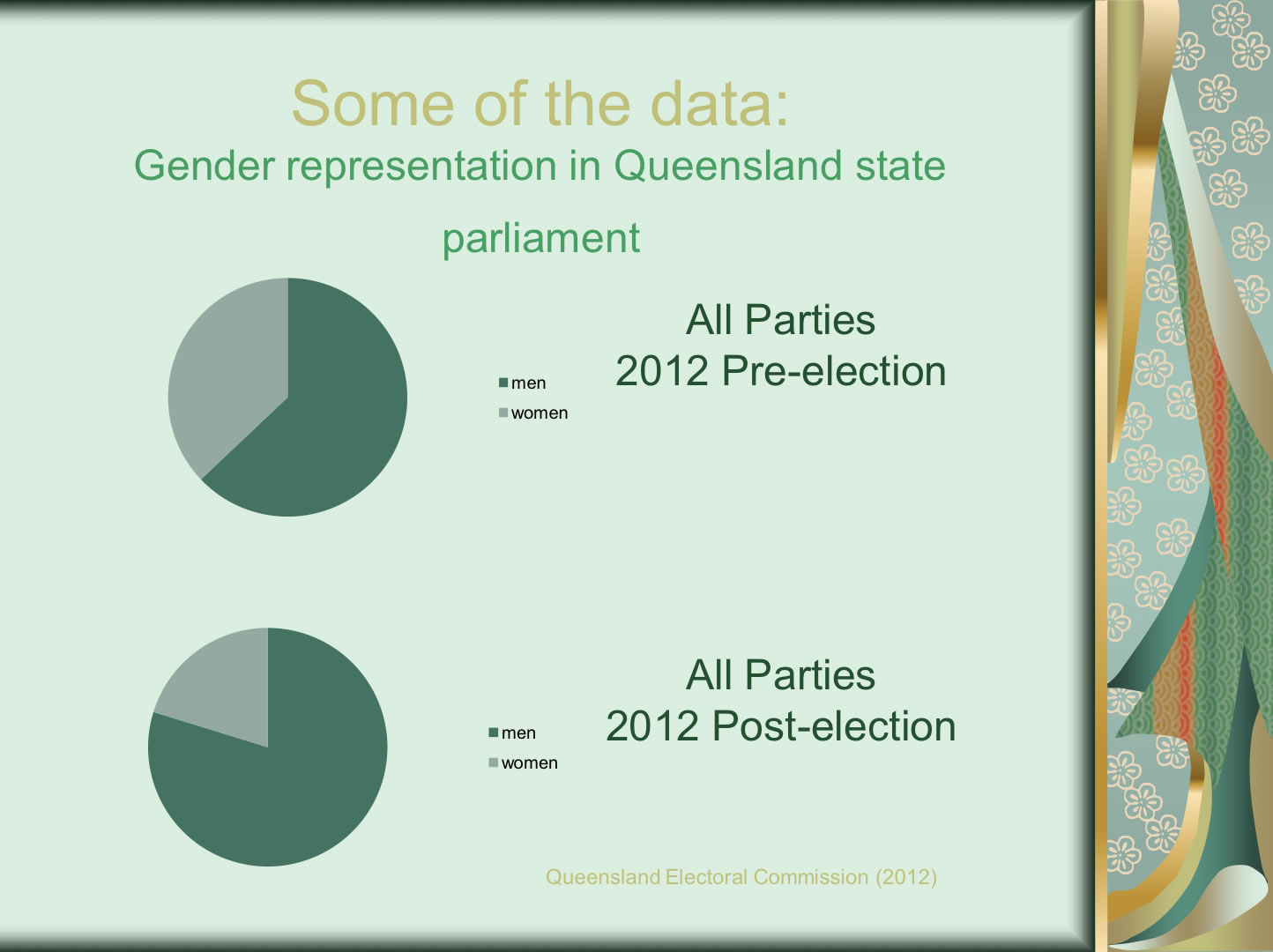

‘Putting gender at top of agenda’ appeared in the Viewpoint pages on January 11 2012. I argued that there was an emphatic warning to Queenslanders that the future trend in state politics was undoubtedly masculine. The predominance of women in leadership belied the evidence that women were already underrepresented in the Queensland Parliament, with women holding a modest third of the seats in the House (Queensland has only a single House at the state level).

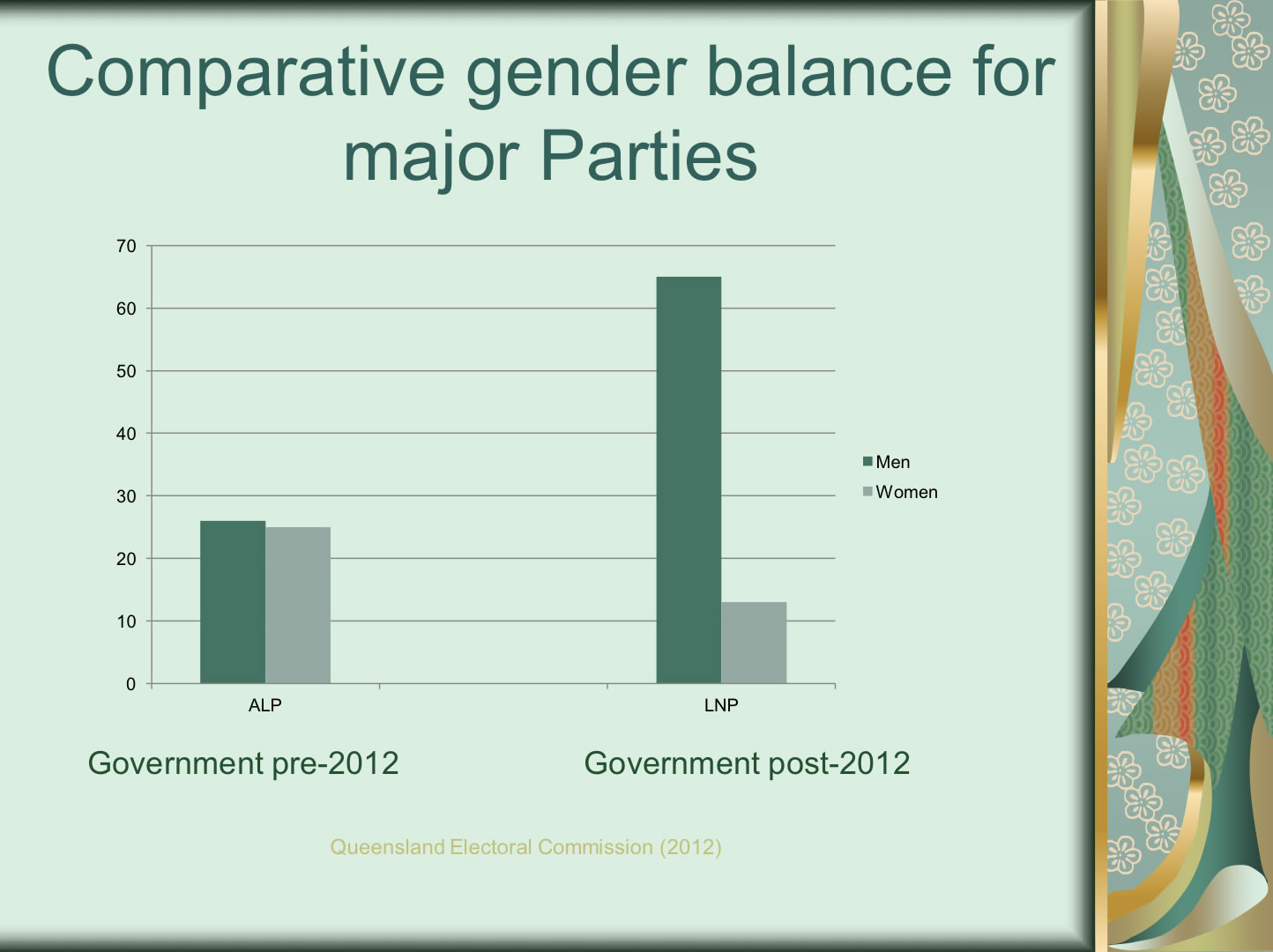

The comparative statistics for the two major parties illustrate a startling inequity: the Australian Labor Party [ALP], which formed the Government, had a 49% representation of women, while the Liberal National Party [LNP] had a mere 14%.

Opinion polls, if they had any credence, predicted a decisive electoral swing to the LNP and the new conservative Katter Australian Party [KAP] in the forthcoming election, with a subsequent decrease in ALP seats, particularly the ‘marginals’ held predominantly by women.

I argued that the status of Queensland women on a range of fundamental markers was already precarious when compared to other Australian states, and unlikely to be improved by regressive politics. For example, Queensland women score poorly on the availability of full-time employment; they suffer the highest gender pay gap; they feature prominently in statistics relating to sexual assault and violence and murder by their partners; and, unlike other states, the criminal code denies them reproductive autonomy.

A swing against the ALP, combined with a resurgent conservative vote, had the potential to stifle and eliminate gains women had made, especially in the provision of health, employment and education services. At that time, the predominance of males as candidates for both the LNP and the KAP suggested that Queensland women should be prepared for a significant alteration to the gender structure of the parliament.

Queensland went to the polls late in March 2012, and the magnitude of the change in the balance of power surprised even the most ardent supporters of the LNP The ALP had been summarily swept aside in a landslide unprecedented in Queensland history, and the devastation of women’s presence in the House became gloomily evident. Regrettably it seemed that the 2012 election would gain notoriety as the year women’s voice in legislative matters was virtually silenced, an observation I shared with Margaret Wenham [Viewpoint editor, Courier Mail]. She suggested a follow-up ed op article would be timely.

The Plot:

My response, ‘Women struggle for a political voice’ was published in the Courier Mail on 16 April, 2012.

These two graphs illustrate the representation of women in the Parliament pre- and post-election, with a decline in the number of women clearly evident from one-third to one-fifth.However, relative comparisons of gender composition of the former ALP Government and the newly-elected Newman LNP Government, was catastrophic. The previous Government benches had boasted 49% women;: the incoming Government, a mere 16%.

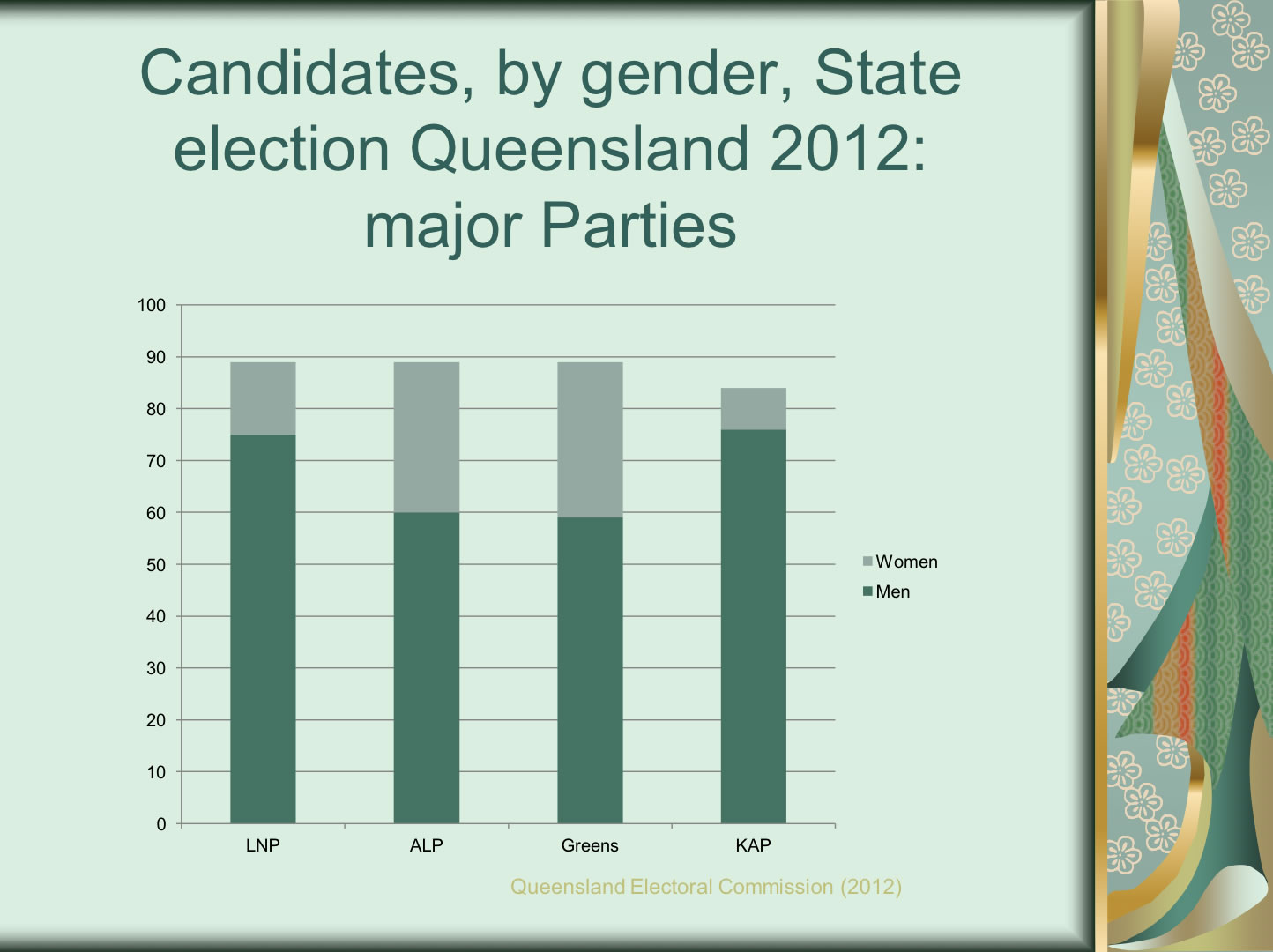

Apologists may consider that perhaps women were not as electorally successful as men. A rudimentary glance at the gender balance of candidates from the major Parties dispels that myth. Women cannot become MPs if they are over-looked at the pre-selection stage.

Premier-elect Campbell Newman lamented that there were few women in his Government, but the LNP has no strategy to ensure the recruitment and encouragement of talented women. Of the 89 LNP candidates, only 14 were women; and the new KAP could only find 8 meritorious women 9out of 76 nominations) among its ranks.In the article I outlined that I was not promoting tokenism. Female candidates should be scrutinised in exactly the same way as male candidates, based on their capabilities and personal characteristics, but unfortunately sexism and gender discrimination are persistent. It is improbable that intellectual capacity, business acumen and political aptitude are solely the province of men and that somehow, the absence of women from the political process is not a result of systemic exclusion and subtle – and not so subtle – stereotyping.

The conflict:

As anyone who has written for the media, in support of women’s rights, can probably testify, the response is reasonably predictable. Letters to the editor for the ensuing days reflect a mixture of positive and negative ideas, with viewpoints that are diametrically opposite, and with the anti-group often presenting with latent hostility. And initially that was the public response, until i received an email: the subject line, ‘Please get a life’.

I have included sections of the text from the email, which expounds very emphatically, the error of my ways! To the writer’s credit, he did include his name and telephone number. I was incredulous at the outdated nonsense – twaddle – in his rant, but realised that this personal invective was intended to chastise and demean. Surely the rant of a bully. I did call the writer, optimistically, for an apology, but he ‘didn’t like my tone’.

A ‘google’ revealed that the email was from a former sub-editor of a newspaper who was currently employed as the media adviser to a Liberal Party Senator, and although he had not written in his official capacity, he would have been well aware that his action was unethical.

Taking to heart his accusation that ‘demonising men was my life’s quest’ I forwarded his email to a number of email networks; those members shared it with their networks; and they shared it . . . and so on. Evidently someone shared it with the media, who approached Federal Opposition leader Tony Abbott for comment. His summation that it was entirely inappropriate culminated in the media adviser resigning his position, and me experiencing my fifteen minutes – or in this case thrity minutes – of fame.My email inbox went into meltdown and the phone rang constantly, with messages of support from friends, acquaintances and strangers alike, and requests from the media Australia wide. Remarkably not one adverse personal message and even twitterers and facebookers were almost universally in agreement. One voice of dissent, registered in the Townsville Bulletin, belonged to a local medico Greg canning, responsible for an extensive men’s online website.

He lamented that Mr Tomlinson was being ‘publicly vilified for daring to hold a view counter to the dominant narrative of gender as asocial construct’ and emotively accused me of ‘leaking’ personal correspondence to promote a ‘classical case of feminist dogma’. He was particularly distressed by use of what he referred to as the ‘intellectually embarrassing term PMS’, as shorthand for patriarchy, misogyny and sexism, which in his opinion are no longer restrictive of women’s status. The term, devised by US feminist activist Marcia Dyson, seemed a perfect appropriation and renaming of an acronym that is invariably directed at women.

In the post-election article, I had also been critical of the LNP’s lack of a cohesive women’s policy and a range of ministerial appointments by the Newman government which terminated the role of Minister for Women – although there was an Assistant Minister for racehorses. (The Premier’s rather lamentable response when asked about this apparent degradation of women’s rights even provoked censure from the Federal Minister for Women).

Additionally, I affirmed that despite decades of universal suffrage, the man-as-norm in politics persist, and the election of Newman and his conservative colleagues demonstrated the tenuous connection women have with political representation. In less than two months in power, we have evidenced the defunding of “sisters Inside’, a grassroots support group for women exiting prison; the closure of Queensland Association for healthy Communities, which provides gay and lesbian health services; the reassignment of Regional Coordinators for the Office for Women to other tasks; the possible mainstreaming of sexual assault services; the discontinuation of short-term contracts for frontline public service staff, who are predominantly women; and the very real concern that family planning providers (which includes abortion services) may be in the sights of the slash and burn brigade. In the introduction to my cautionary tale I indicated that this was an autobiographical narrative. However, exploring the concept of the representation of women in the political landscape has been the subject of sustained – and at times contradictory – theoretical themes. I will suggest a few: feel free to add to the list.

- Is gender relevant to modern democratic governments?

Female suffrage has been a factor in the Australian political context for more than a hundred years, and yet mainstream political institutions persist as male bastions of power. Despite an increase in female representation in all tiers of government in the past three decades the organisational processes and practices of the relevant institutions remain staunchly gendered. Previously theory has focused on the presence of a critical mass of women essential to initiate cultuyral change in mainstream politics, but defining precisely what constituted a ‘critical mass’ was particularly daunting. It perpetuated a belief that when women acquired a particular percentage presence in government, miracles may happen.

Social science researcher Sandra Grey presented a paper in 2001 providing a comprehensive overview of factors in the critical mass debate. She argues that despite difficulty in gauging the impact of women in parliaments, numerical strength in legislatures is a viable concept for changing entrenched attitudes and positional power. Regrettably the 2012 election in Queensland demonstrates a system moving backwards (eg Sawer, 2012; Ford, 2012) and as I have indicated, potential repercussions are substantial. Pursuing an increased presence of women in parliaments does not negate merit, although it makes its application problematic: What is merit and who defines it?

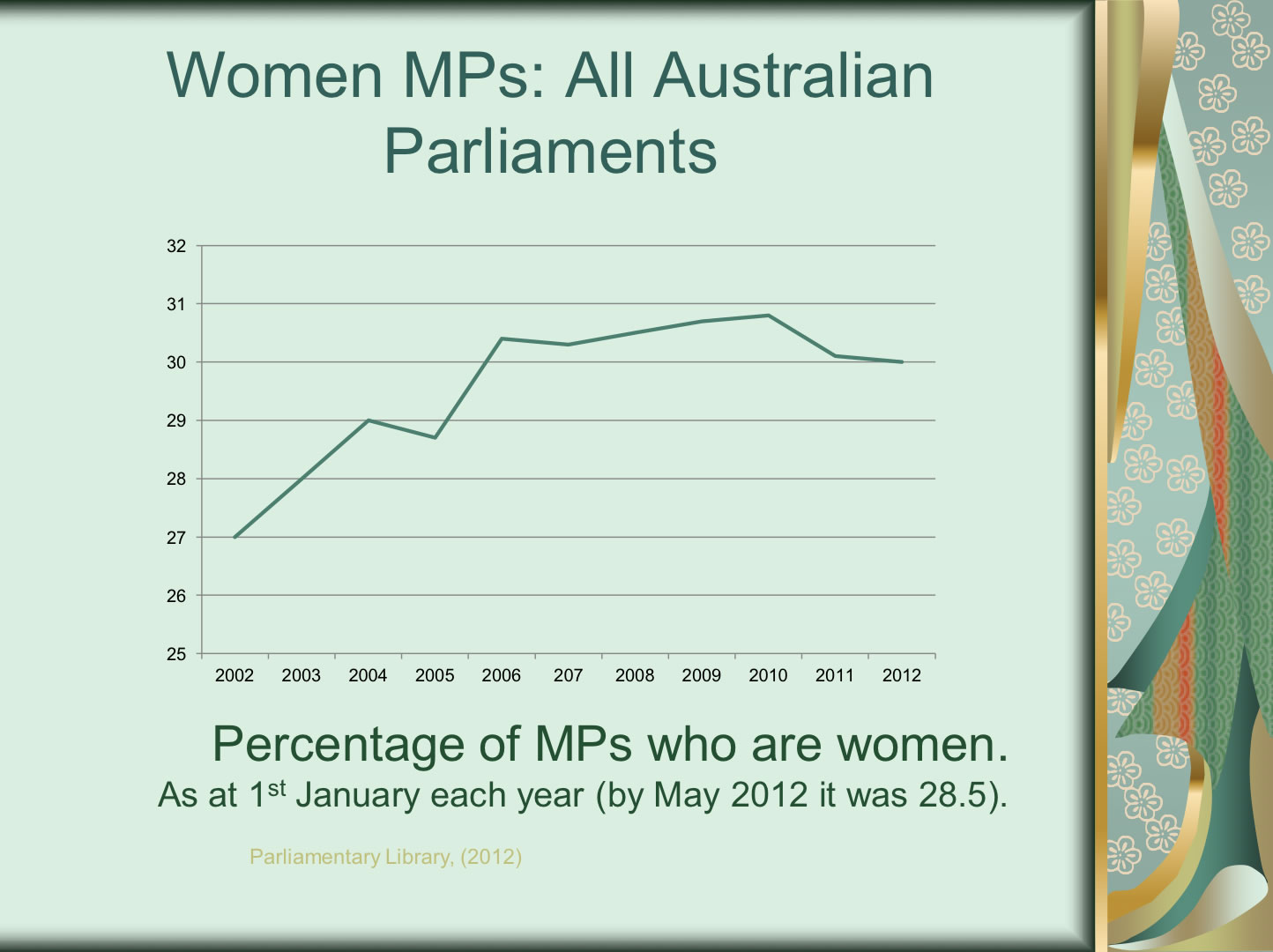

Generalisations regarding statistical data of women in Australian parliaments suggest that overall the movement has stalled. The graph below pinpoints the percentage representation of women in Australian parliaments over the past decade, which has persisted at 30%, although there is evidence of decline in the figure post Queensland election.

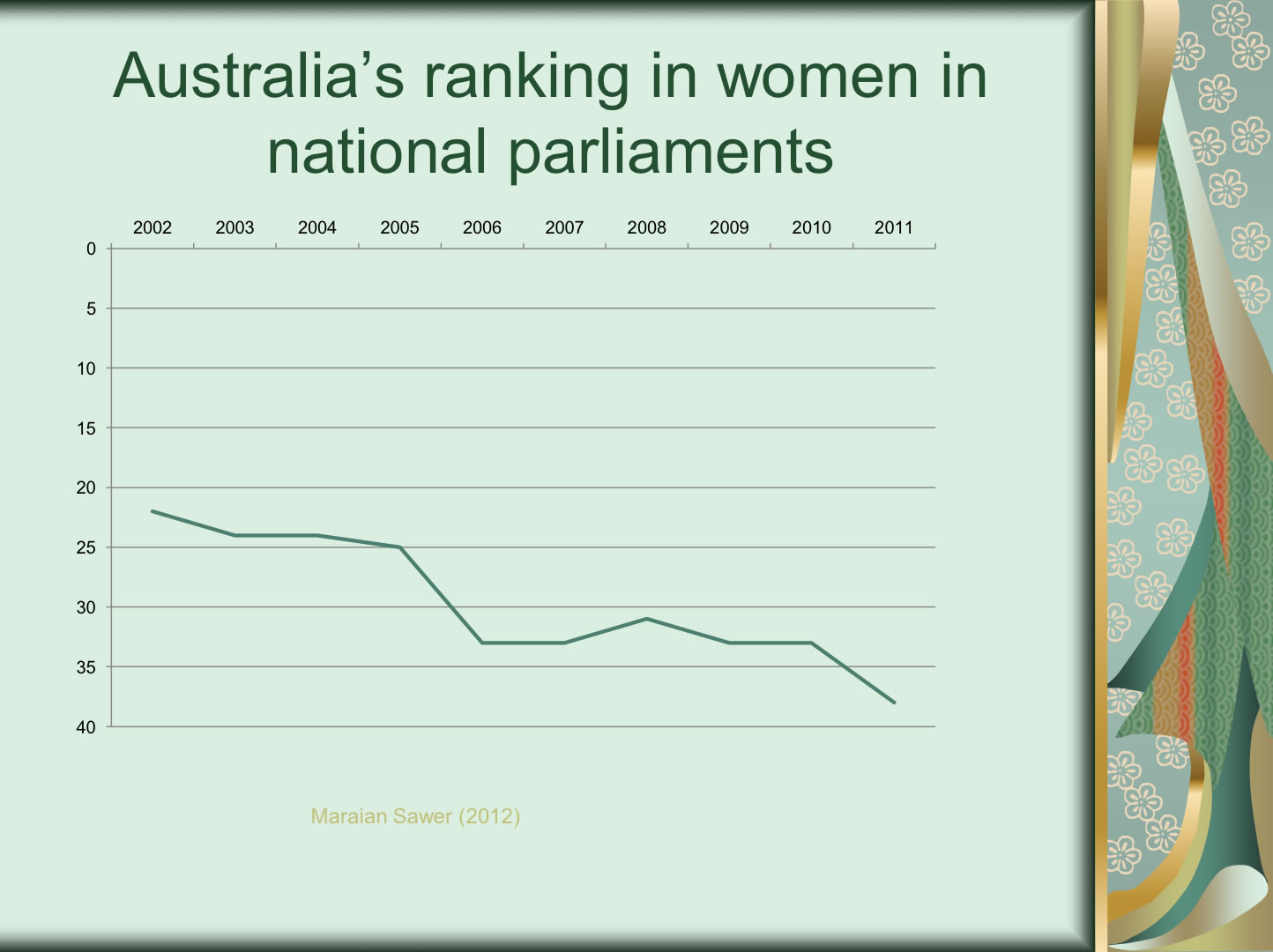

Comparisons at the international level are telling. Despite Australia’s leadership in the implementation of female suffrage, by 2002 they were a modest 22nd in international rankings. A decade later, their position relative to other democracies has declined to 38th, and already figures for 2012 will potentially see our representation of women in parliaments fall to an even lower ranking.

Elizabeth Broderick, the Sex Discrimination Commissioner with the Australian Human Rights Commission, referred to this in an address to an International Women’s Day Forum in march 2012. She quoted feminist legal scholar Sandra Freedman to confirm the link between representation and policy. She commented that

[t]he future is not simply one of allowing women into a male-defined world. Instead, equality for women entails a restructuring [of] society so that it is no longer male-defined. Transformation requires a redistribution of power and resources and a change in institutional structure which perpetuate women’s oppression. It requires a dismantling of the public-private divide . . .

2. The culpability of the media and popular culture

The Canadian Media Awareness Network suggest that journalistic bias and discrimination is not always a conscious act, and indeed it is the unconscious bias that is more insidious. Politics is a traditionally male-dominated field and political journalism employs a masculine narrative and positions man-as-norm. Joanna Everitt (2010) utilised a content analysis to demonstrate the manner in which gender stereotypes are sustained, for example through difference in representation of behaviour during debates: aggressive versus assertive; emotive versus objective; and opinionated versus definitive.

The proliferation of talkback radio and social networking has expanded the opportunities for personal invective – witness the Tomlinson email. This was the basis for my most recent article in the Courier Mail, ‘Attacks on women set an ugly precedent’ where I identified much of the language as violent, and relevant to the continuum of violence perpetrated against women. If detractors are permitted to use implied violent, demeaning and derogatory comment to attack the most predominant woman in Australia [Prime Minister, Julia Gillard] without fear of redress, what hope for every other woman? Consider the potential for bullying and intimidation, particularly through social networking, to ensure that women do not stand up and speak out.

3. Who is responsible for creating systemic change?

We all are!

Joy McCann and Janet Wilson (2012) comment that research suggest that the under-representation of women in our elected parliaments has a significant impact on how women generally perceive their inclusion in society With the election of the Newman government, women in Queensland could be excused for believing they are invisible.